Zeballos-area residents encountered a rare site this morning, as a beached killer whale gave her last breaths while a baby continued to swim around the dying female in the shallow waters.

Kyle Harry is a long-time resident of Ehatis, the Ehattisaht First Nation’s reserve community located right next to Zeballos. He said the orcas were first seen at 7 a.m. by Glenn McCall, who maintains the road to Ehatis. They were sighted by the Causeway bridge, a shallow portion of the Zeballos Inlet that’s approximately a 10-minute drive from the village.

“He went to everyone’s doors, to chief and council’s doors and our fisheries to let them know the whale was on the beach,” said Harry, who first heard of the incident through Facebook when he awoke at 8:30 a.m.

Harry soon joined those at the site in an effort to keep the female alive.

“When we got there the killer whale had a dead seal in its mouth, there was body parts of the seal around it,” he said. “So, it was hunting and it was probably teaching its baby how to hunt, and then it ended up on the beach.”

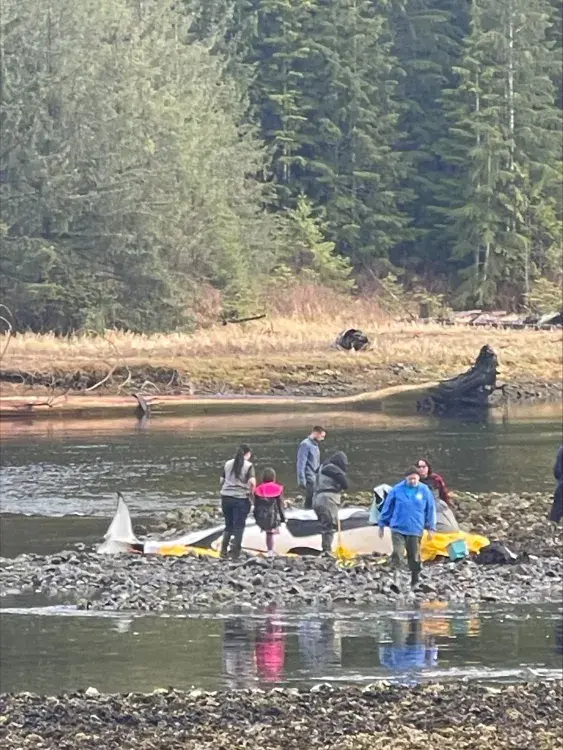

Dozens of locals were soon on the beach, including residents of Ehatis, Ehattesaht’s elected chief and council, Zeballos residents and people living in the nearby Nuchatlaht community of Oclucje.

Also present were Judae Smith and Rob John, who have been trained in responding to stranded marine mammals, said Harry. They were instructing others in what to do.

Those on the scene worked to keep the female wet with buckets and soaked towels. Video footage shows the grounded killer whale, or kakawin in Nuu-chah-nulth, on her side desperately splashing water with her tail.

“We were trying to flip the whale on its stomach before we lost it,” said Harry, adding that they ceased this effort at 10:20 a.m. when it appeared the female had passed. “The mother is dead now, but the baby is still there swimming around it.”

“Despite the intensity of effort to rescue her, the mother has drowned,” states an update from the Marine Education and Research Society. “The calf is nearby.”

“It was devastating, my heart was gasping for air, knowing that there was a baby there,” said Ehatis resident Jessie Mack, who was among those on the scene.

“The incoming tide and inability to refloat her, so she was not on her side, led to her death,” stated MERS on a social media post. “We will update here with anything we learn, including her ID.”

Those present notified Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and staff were on their way to assess the orcas.

“I got a message asking information for the DFO also,” said Mack, who heard that the baby could be transported to an aquarium.

Mack has lived in Ehatis for 12 years, while Harry has been in the community since 1999. Both have never encountered a beached orca in their territory, but Mack noted that others from the First Nation spoke about whales getting stranded in the shallow Causeway area many years ago.

“This area is known to us. It is highly influenced by changes in tides,” stated MERS. “The whales would have come in on a high tide (possibly hunting). When the tide ebbs in this particular spot, it happens very quickly.”

DFO officials have yet to identify the animals, but descriptions of the orcas indicate they could be transient killer whales, which feed primarily on marine mammals like seals and sea lions. The killer whales are listed as “threatened” under Canada’s Species At Risk Act. The last formal count in 2011 indicated just over 500 transients in Canadian waters.

“Although they are occasionally seen in Washington, Alaska, and California, transient Killer Whales in Canadian Pacific waters are non-migratory and spend the majority of their life within the coastal waters of British Columbia,” states the DFO’s information on the species.

Also called Bigg’s killer whales, transients differ from southern and northern resident killer whales, which exclusively feed on fish, primarily salmon.

“Research suggests that Transients have been genetically separated from all other killer whales for about 750,000 years,” stated the DFO.

As the baby continues to live, some of those present at the scene went out in boats to try and locate a pod that may help the young one survive, according to reports.

“Survival of the calf will depend on their age (independence) and the family structure of these whales,” stated the Marine Education and Research Society. “Not all Bigg's organize in matrilines whereby there might be family members nearby.”