There is a heart fence in Port Alberni that memorializes some of the loved ones who have died due to the illicit drug supply in the past few years. The Heart Project features brightly coloured wooden hearts hanging from a chain-link fence at Dry Creek Park off of 4th Avenue.

But the few lovingly hand-painted wooden hearts represent only a small number of the lives lost to the opioid epidemic in Port Alberni since 2014. The actual number of lives lost to illicit drugs in the 11 years since the start of the opioid epidemic in the Alberni Clayoquot Local Health Area, which includes Tofino and Ucluelet, is likely in the hundreds.

In British Columbia alone, 17,683 people have died due to the toxic illicit drug supply since 2014 and the number continues to grow daily. Compare that to the City of Port Alberni’s population of just over 18,000. The overdose crisis has been a provincial public health emergency since 2016, and a federal report states the leading cause of death in British Columbia last year continued to be accidental poisoning due to illicit drug toxicity.

But there may be some light at the end of tunnel. In its latest report on deaths related to unregulated drug toxicity, the BC Coroner’s Service is showing for the first time in years a reduction in the number of deaths in the first quarter of 2025 compared to the previous year.

The provincial health authorities are seeing a monthly death toll from illicit drugs fall below 160 for as many as six months in a row. In January 2024, 219 deaths from illicit drugs in B.C. were recorded while there were 152 deaths recorded for the same time period in 2025.

In 2023 the Alberni-Clayoquot local health area was ranked third following Vancouver’s Downtown East Side for the most illicit drug deaths per capita.

For that reason, several concerned leaders and residents have come together to look for solutions.

The Port Alberni Community Action Team is a locally led initiative responding to the overdose crisis. A peer-driven team, the Port Alberni CAT works collaboratively with emergency services and first responders, “with a focus on family support, strong relationships with local Indigenous partners and First Nations Health Authority.”

According to Port Alberni CAT, a 25 per cent drop in the rate of drug poisoning deaths so far this year in British Columbia “is being attributed to factors ranging from a decline in the fentanyl concentration in the drug supply to harm reduction measures, such as wider availability of the drug-overdose reversing drug naloxone.”

There are many factors that could be contributing to the decline in deaths. Changing drug regulations could have altered illicit drug recipes, while to harm reduction measures such as outreach, safe supply and overdose prevention sites have focused on keeping user alive.

In September 2024 the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council declared a state of emergency, calling for dedicated and substantial funding to adequately provide meaningful and culturally appropriate trauma-informed services to Nuu-chah-nulth communities. They say that the opioid and mental health crises affect First Nations communities disproportionately.

In late May Nuu-chah-nulth leaders got together for a two-day meeting to strategize, with a focus on saving lives. While everyone is cautiously optimistic about the news that drug deaths have lessened, it comes with the knowledge that there is still much work to do.

One of the concerns is that the unregulated drug supply is just that – formulations are changing all the time.

“They’re mixing other things in, and Naloxone doesn’t work,” said NTC President Judith Sayers about the latest mixtures of illicit substances available.

She learned that it is important for people to know how to resuscitate an unconscious person when Naloxone isn’t working.

“You need to help them breathe until help gets there,” Sayers said.

During the Nuu-chah-nulth leaders’ meeting on the toxic drug crisis, several actions were identified, like raising awareness, using a blend of traditional and modern healing/helping methods.

“We have excellent partners and together we can do this,” said Sayers, adding that until the death rate drops to zero, there will always be concern.

Despite the reduction in illicit drug deaths, the latest numbers from February and March 2025 mean an average of about five deaths a day in the province. For comparison, in 2024 there was an average of six deaths per day and, at its highest point, seven deaths per day in 2023.

Ron Merk is the editor of Learning Moments and a long-term advocate for people with concurrent disorders and evidence-based drug policies in B.C. He says death numbers may have dropped because it appears fentanyl content in the drug supply has lessened somewhat.

“But Port Alberni is still a hotbed and there’s still significant risk,” said Merk.

Merk said that a request for proposal was sent to Island Health in 2024, seeking eight to 10 recovery beds for Port Alberni, but he doesn’t know what is happening with the proposal. He said Port Alberni and region is in desperate need of recovery beds that anyone can access.

Pointing out that Port Alberni has only one psychiatrist, he said it would be nice if we had one more.

While the news that there are fewer drug deaths in 2025 is good, Merk hopes the numbers continue to drop so that it can be called a trend.

“We have lots of work to do,” he said.

According to the BC Coroners Service, fentanyl and its analogues continue to be the most common substance detected in expedited toxicological testing.

“More than three-quarters of decedents who underwent expedited testing in 2025 were found to have fentanyl in their systems (70 per cent), followed by methamphetamine (50 per cent) and fluorofentanyl (47 per cent),” stated the coroner.

The cities experiencing the highest number of unregulated drug deaths so far in 2025 are Vancouver (97), Surrey (52) and Greater Victoria (28).

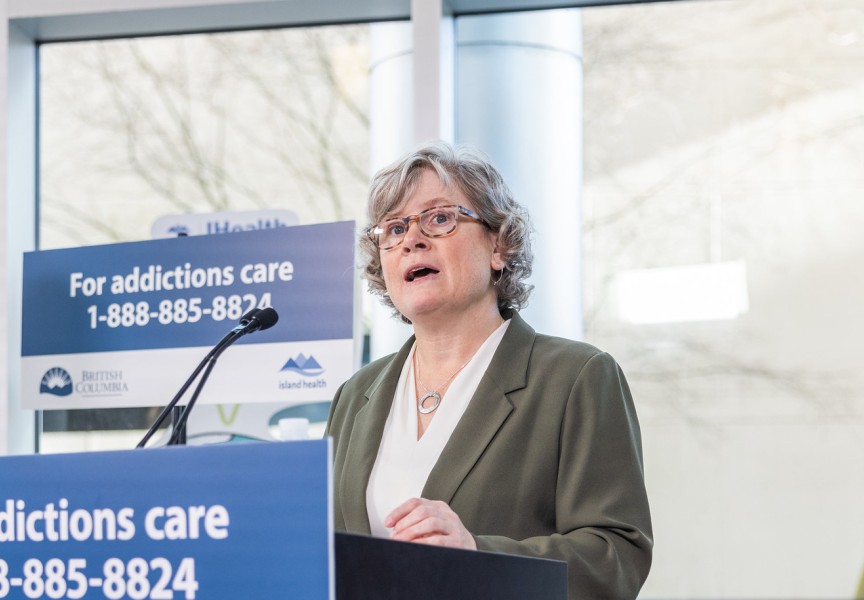

Dr. Alexis Crabtree, a public health physician, said overall the numbers represent a 25 per cent decrease in the rate of drug-poisoning deaths in 2025 compared with the prior year, and a 36 per cent decrease from the peak in October 2023.