– Recent reports of a pack of sea wolves in the Pacific Rim corridor acting habituated towards humans has prompted Parks Canada to issue a public reminder about how to stay safe and respect these animals.

Francis Bruhwiler is a specialist in human-wildlife co-existence in Pacific Rim National Park Reserve (PRNPR). He says the pack is likely the same two or three coastal wolves acting “very indifferent” when they see people.

“If you want to break that down, it’s a loss of the natural human fear we would like them to have,” said Bruhwiler. “That behaviour is concerning because of that loss of that wariness towards humans. It seems like it’s faded a little bit.”

“Habituated wolves have been happening for at least 30 years,” he continued. “We’ve had way worse. In 2017, they were in parking lots. It’s not there, we’re not there, but we don’t want to get to that place. If everyone can take this seriously, we feel like that wariness of humans that they need can be maintained.”

The human-wolf interactions started back in April when a pair of wolves showed up in downtown Tofino, according to Bruhwiler.

“There’s a lot of food in those communities. And I’m not talking human food, I’m talking about dogs, cats, racoons, deer… There’s a lot of prey right where we live and I think that’s what people have to remember,” he said.

Sea wolves primarily eat a marine-based diet; they are known to feed on otters, salmon, harbour seals, herring eggs, clams, mussels and whale or sea lion carcasses. They also go for racoons, small deer and injured black bears or cubs.

Another April dispatch to Parks Canada involved a wolf walking by a visitor in the PRNPR without any fear.

Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation also posted a bulletin on their community board on May 2 asking residents of Esowista and Ty-Histanis to walk in groups or pairs while being careful and diligent, particularly at sunset and night. A pair of wolves were regularly sighted in the communities, which are located just north of Long Beach.

How to reduce human-wolf conflicts

“Put your dog on-leash. That’s a big one. A dog on-leash is way safer,” says Bruhwiler. “I’ve seen big dogs killed here by wolf. I’ve seen dead dogs. We don’t want to go back there. This is what we are trying to avoid.”

Managing all attractants like putting food away before going out for a surf and not going up to the animal to take photos will also help keep the “wild in wildlife”, notes Bruhwiler.

“Let’s say a wolf is on the beach and around, the best thing we can do is make it obvious that we don’t want it nearby. Make noise, group together. Exactly like seeing a black bear. If the wolf is there and doesn’t want to leave then we leave,” he said.

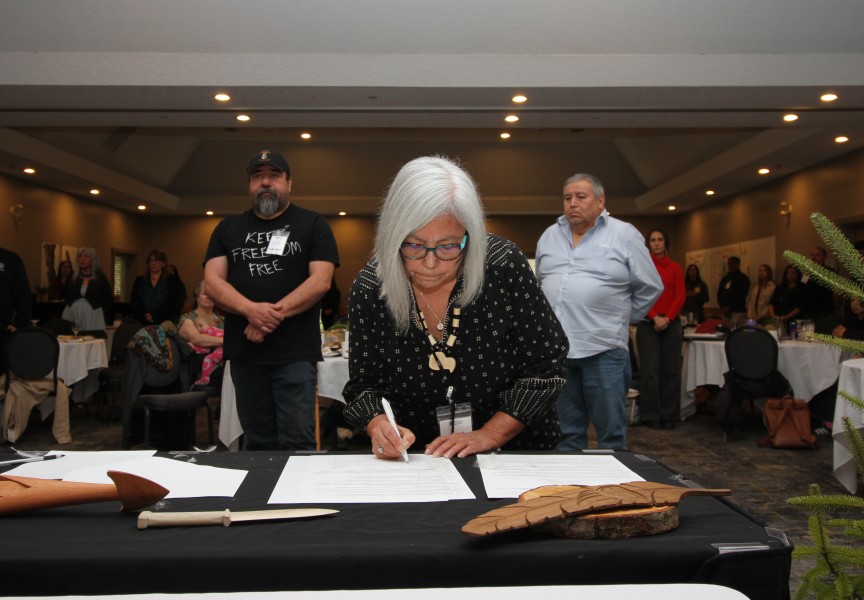

Parks Canada works in collaboration with Tla-o-qui-aht and Ucluelet First Nation to monitor the wolf activity in the region.

Wolf in Nuu-chah-nulth language is qʷayac̓iik (pronounced qwa-ya-tseek).

“We have a lot of strong teachings from wolves in Nuu-chah-nulth cultures across many nations and families,” said Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks Guardian Gisele Martin. “A lot of teachings have to do with respecting natural law, with upholding traditional ecological roles or about doing the things that need to be done to make things right in this world, is associated with wolves.”

She explained that it is against Nuu-chah-nulth traditional law to harm or disturb wolves.

“It’s also part of our culture to give wolves right of way because they are so integral in maintaining the balance of life in nature. They have the same role in ocean as orca whales,” said Martin. “If you encounter a wolf, back up. Give them the right of way. Don’t be wolf paparazzi.”

Martin shared that the “qʷa” in the Nuu-chah-nulth word qʷayac̓iik (wolf) is seen in other words or phrases that translate to “be good like that”, “things that we need to do to make things right in the world” and “bow of the canoe”.

“The bow of the canoe, that’s what gives us direction and is shaped like the head of a wolf,” said Martin.

In June 2024, the ʔapsčiik t̓ašii Trail (pronounced ups-cheek ta-shee) multi-use pathway that connects Ucluelet to Tofino was officially opened, creating an influx of cyclists through the Pacific Rim corridor. The paved pathway is roughly 40-kilometres long and weaves through the traditional territories of the Tla-o-qui-aht and Yuułuʔiłʔat as well as the shoreline in the Long Beach Unit of Pacific Rim National Park Reserve.

“The trail definitely has an impact on the land and the place,” said Martin. “The Banana slugs who cross it, they have important duties to do in the forest. It’s just not the wolves; it’s everybody that lives there. It’s something to be mindful of.”

On May 7, a deceased juvenile gray whale washed up on Long Beach and is still on the landscape, but the carcass is not “readily available to wolves”, according to Bruhwiler.

“With the whale that washed in, we did not have any wolf interactions at that time. They are their own little minds and maybe they had other things on the go,” he said, adding that sea wolves are incredible swimmers and could travel from Long Beach to the Broken Group Islands in days.

Martin encouraged people to familiarize themselves with the ʔiisaak (ii-saak) Pledge, which outlines respectful behaviours and practices that can be used as guidance on how to relate to wolves and wolf habitat.

“Every plant and animal, living being, every insect, has something important that they contribute to the community of life. Wolves are really integral to that whole process,” Martin said.

If you see or encounter a wolf in the Pacific Rim National Park Reserve, report it Parks Canada dispatch at: 1-877-852-3100.