For those who rely on the ocean’s resources for sustenance, a succession of fisheries restrictions has created a daunting scenario this spring on the West Coast.

In late April Fisheries and Oceans Canada announced strict measures to protect endangered chinook salmon originating from the Fraser River. For most fisheries, including those in offshore areas west of Vancouver Island, chinook retention isn’t permitted until at least July 15. This also pertains to fish caught for First Nations food, social and ceremonial use (FSC). Commercial fisheries are being pushed back to August for chinook.

Then as part of its effort to protect the endangered southern resident killer whale population, the DFO recently stated that no fishing or any vessels will be permitted in the orcas’ sanctuary zones off of Pender Island, Saturna Island and Swiftsure Bank, an offshore area located directly west of Nitinat Lake. Emergency vessels and First Nations FSC have been granted exceptions to this restriction.

“Fraser River chinook are the main food source of the endangered southern resident killer whales,” wrote Lara Sloan, DFO communications officer, in an email to Ha-Shilth-Sa. “Ensuring that the orcas have enough food and the best conditions to forage is key to their recovery, and we are committed to doing everything we can to help protect these whales.”

But as scientists and regulators look into how to better manage the ecological balance in favour of southern resident killer whales, some believe that a key factor is being left out of the equation. Chinook salmon are part of the diet of seals and sea lions, two species that have seen a population growth since hunting was banned a half century ago on the B.C. coast.

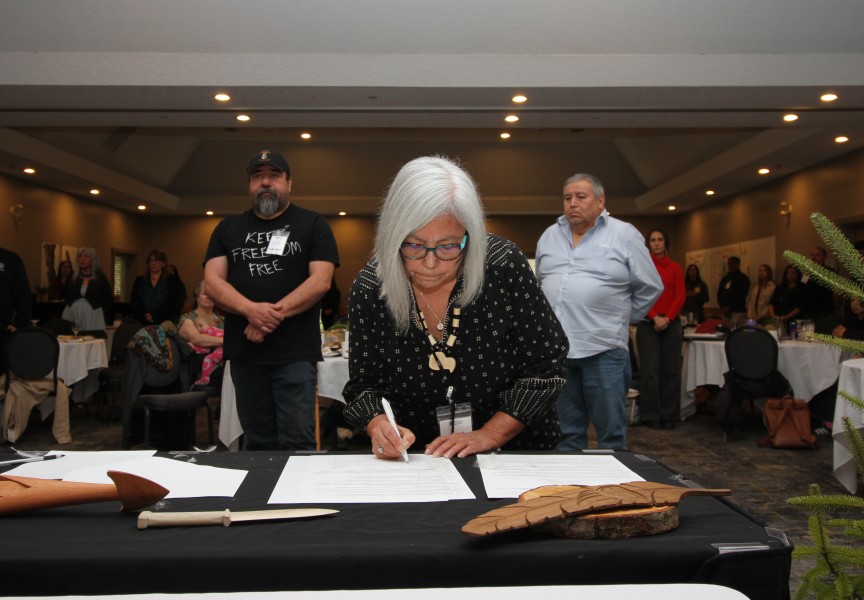

Larry Johnson, chair of the Maa-nulth Treaty Society’s fisheries committee, is looking to develop a plan that brings back the controlled pinniped harvest that was part of Nuu-chah-nulth life for thousands of years.

“We want to call it a management plan to put balance back into what our traditional roles were,” he said. “None of us want to see the killer whales disappear, but we also know that we need to manage within the Nuu-chah-nulth principles, how everything is connected.”

The Assembly of First Nations is behind this approach, with a resolution passed in July 2018 at its annual general meeting that calls for First Nations to work with the DFO to “implement targeted management strategies in regard to the growing population of seals and sea lions throughout the entire B.C. coast.”

Since the harbour seal hunt ended in 1967, the population on B.C.’s coast has grown tenfold to approximately 100,000.

And the stellar sea lion’s numbers have also increased in coastal B.C. The current estimate is 19,700 during the summer breeding season, more than twice the counts recorded when the animals became protected in 1970.

“Seal and sea lion populations then grew exponentially per year during the 1970s and 1980s, but growth rates began to slow in the 1990s for harbour seals, and the population now appears to have stabilized,” explained Sloan. “Sea lion population continues to increase. Both species are believed to be at or slightly above historic norms.”

Governments continue to pour money into supporting the recovery of southern resident killer whales and the salmon they feed on, with a $5-million investment from the provincial government to the Pacific Salmon Foundation being the most recent mark of support announced on May 16.

But Johnson questions how much of the ongoing population restoration work is being offset by the voracious diets of seals and sea lions. A harbour seal can eat up to five kilograms of fish in a day, while an 800-kilogram male sea lion regularly consumes 50 kilograms of fish.

“Without dealing with pinnipeds right away as a short-term measure, are we shooting ourselves in the foot by not protecting our investments in terms of salmon enhancement, salmon habitat and production?” asked Johnson. “It’s a guessing game. Are we really just putting more food into the pinnipeds?”

Although the DFO has “no plans to authorize a large-scale” seal or sea lion hunt, the federal department is looking at proposals, said Sloan. She noted that ongoing studies in the Strait of Georgia show that salmon comprise less than 10 per cent of harbour seals’ diet, as the animals in that region primarily feed on hake and herring. Further research is planned on the diets of West Coast pinnipeds to inform future policy.

“Fisheries and Oceans Canada has received a proposal from the Pacific Balance Pinnipeds Society to create a commercial fishery for pinnipeds under the department’s New and Emerging Fisheries Policy,” wrote Sloan. “DFO intends to take an ecosystem-based approach to fisheries and oceans management to ensure that the best science is reflected in consideration of the role seals and other marine and aquatic species play in sustaining a healthy and productive aquatic ecosystem.”