A “fireworks display of possibility.” This is how Dr. Andrea Walsh describes the legacy that has come from the repatriation of residential school children’s paintings done in a ceremony held March 30 at Alberni Athletic Hall.

“I was struck by the way in which the stories of the paintings move on,” she said. If they had stayed within the university, then the paintings’ story would have ended there, Walsh explained.

Walsh, a visual anthropologist with the University of Victoria, has been the one responsible for the safekeeping of the paintings, produced by students attending the notorious Alberni Indian Residential School (AIRS) between 1959 and 1966.

Stuck in a drawer away from the public, the paintings may have been preserved, but that’s it. Now there is a momentum to the paintings, said Walsh. There are “profound implications” as their story becomes part of the larger discussion about residential schools, and a part of individual families’ histories, Walsh said.

The repatriation, she said, “was the right thing to do.”

See photos: http://www.hashilthsa.com/gallery/repatriation-childrens-residential-school-paintings

The university had been given the collection of paintings—47 in all—after the death of volunteer art teacher Robert Aller. He had asked each child in his class to give him one of their paintings to keep.

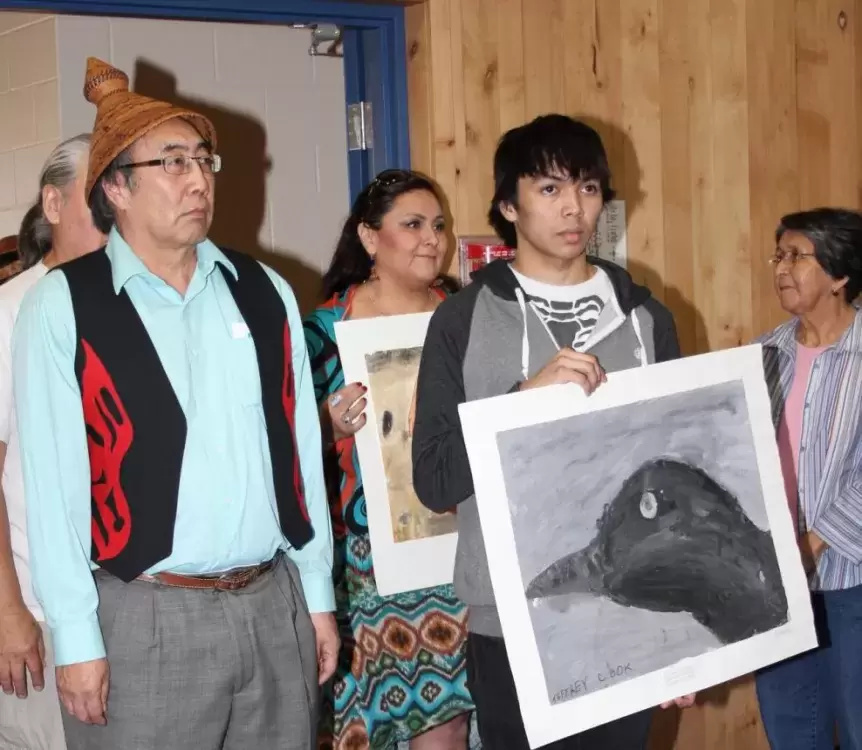

Those paintings were reunited with their now-adult artists, or their representatives, during a ceremony filled with emotion. The original paintings were walked into the hall beside their artists and behind Nuu-chah-nulth drummers. The originals were then placed beside framed copies of the art that lined one wall of the gym.

After the protocols of welcome were done, each of the artists was called up to receive his framed copy and to say a few words to those who had come out to witness the event. The artists were also asked to tell Walsh what they would like done with the original.

They could either return it to the university where the paintings have been stored for some years, or they could keep the art work for their own purposes.

For two years Walsh has been trying to find the artists and learn more about the work. Not all the paintings are happy, she said, but the work springs from the individual, self-determined thoughts of the children in that class, some having endured such terrible violence in the school.

Walsh said some of the artists remembered in great detail their reasons for choosing what to paint. There are landscapes and fishing boats, cultural items like a hinkeets headdress, and representations of the natural world. Some students hardly remember attending the class at all.

Huu-ay-aht Ha’wilth Jeff Cook was first to receive his framed copy of his art, choosing to leave his original painting of a black duck with Walsh, on the condition that he can access it when he wants; “no questions asked.”

Ron Hamilton, who spoke for the Ha’wilth, explained that Cook was somebody who came from somebody.

“These were made by people who have a history,” Hamilton said of the paintings. The black duck is important to the people of the west coast, he explained. “We get happy when we see them… joyful.”

“He must have missed duck soup,” Hamilton said.

Cook has said that he became very emotional when he saw the painting. Residential school children have little but their own memories of their school years. Nothing brought home to hang on the fridge. Nothing to keep in a box to show the grandkids.

So important is the painting to the chief that he intends to reproduce it on his curtain, which will become part of the family’s legacy and talked about whenever that curtain comes out.

“That was huge,” said Walsh about Cook’s announcement at the ceremony.

Tyee Ha’wilth Maquinna Lewis George of Ahousaht will also leave the originals of his artwork with the university, at least until the Nuu-chah-nulth build their own museum or cultural centre where the paintings can be housed. But there was also another condition that the university must adhere to. His story of that time, in his own words, must accompany his paintings, one of a Halloween pumpkin and one of his father’s fishing boat.

“The best time of my life—the best time in my life—was fishing with my dad,” Maquinna said. He said he wished he had the painting when Ahousaht was fighting the government, as part of the larger Nuu-chah-nulth litigation to recognize their right to a commercial fishery. “Because we are fishermen.”

Maquinna had never told his story about residential school publicly. He wasn’t done with his healing, he said, but he wanted to share.

When he was about six years old and attending AIRS, he got up early one morning to use the bathroom. A supervisor decided to teach Maquinna a lesson about school rules. Maquinna said the supervisor told him to never, ever go to the bathroom again without his permission.

“He said ‘pull down your pajamas,’ and he strapped me. That’s the story that goes with (his paintings),” said Maquinna. “It’s been a long time…Trying to be strong, but it’s OK to let the tears flow,” he said composing himself. “When you want to go and use the washroom, nobody can say you can’t.”

“It’s critically important to him, that along with those paintings go his story—unchanged—in his words, not prettied up in any way,” said Hamilton on behalf of the Tyee Ha’wilth. “They will be his words and no one else’s.”

Walsh said the story of all the paintings has likely deepened the understanding of residential schools in the general public, the dominant narrative of which is one of government policy, assimilation and abuse. It is about thousands of students, rather than individual experience.

The paintings engage people differently, allows communication on a different level.

“Art does that,” Walsh said.

The family of art teacher Robert Aller was in attendance to witness the repatriation, and Walsh said they were deeply moved on hearing the stories of the paintings, telling her that Aller would have “really approved” of what was done March 30. He had always spoken so well of the children, Walsh said, and he would have approved that their work had gone back to them.

Aller provided a safe space for the First Nations children from AIRS to create; to see something in their mind’s eye and put it down with paint on paper without fear of reprisal.

Charlie Max Lincoln of Kincolith in Nisga’a territory said Aller had told him to ‘draw whatever your heart feels.’ His picture was brightly colored with rockets heading to the moon, an eagle for his mother, and the boat of his father.

The art classes allowed the children to remember the people they came from; unlike the school environment where children were strapped for any infraction, including speaking or singing in their traditional languages, he said.

Not all the former students survived to have their paintings returned to them. Shelley Chester never knew her mom, Phyllis Tate, who gave her up for adoption right at birth. Still, seeing Tate’s paintings was an emotional experience. Chester choked up when declaring she didn’t know what she wanted to do with the originals.

“To touch something that she created is really something,” Chester said.

For those who would like to see the paintings, but missed the repatriation ceremony, they will be on display at UVic’s Legacy Art Gallery located at 630 Yates St. starting May 8. It will be a mix of originals and copies of the work that individual artists have decided to take home with them. An honoring ceremony will be held for the artists at Legacy in June.

Related: http://www.hashilthsa.com/news/2012-04-15/marks-left-children-communicate-difficult-time-past