A study into a rare liver disease has identified First Nations people as being at especially high risk of developing it. Even more interesting, coastal First Nations, including the Nuu-Chah-Nulth, are at the highest risk of all. The study has been ongoing for a few years, and researchers have had to change their focus to include prevention, as well as management once a patient develops the disease, while they continue to search for more insight into the causes.

“GP (doctor) Harvey Henderson… was the one who had seen many of these patients from Ahousaht and other areas like Nuu-Chah-Nulth communities, and he knew of a lot in the Victoria area. So there was this alert that there could be a genetic predisposition,” said Dr. Laura Arbour, lead researcher on the study. “In families, you wouldn’t expect more than a rare sibling or aunt or niece to have it, so multi-generational families with it suggested a higher chance of a genetic factor,” she said.

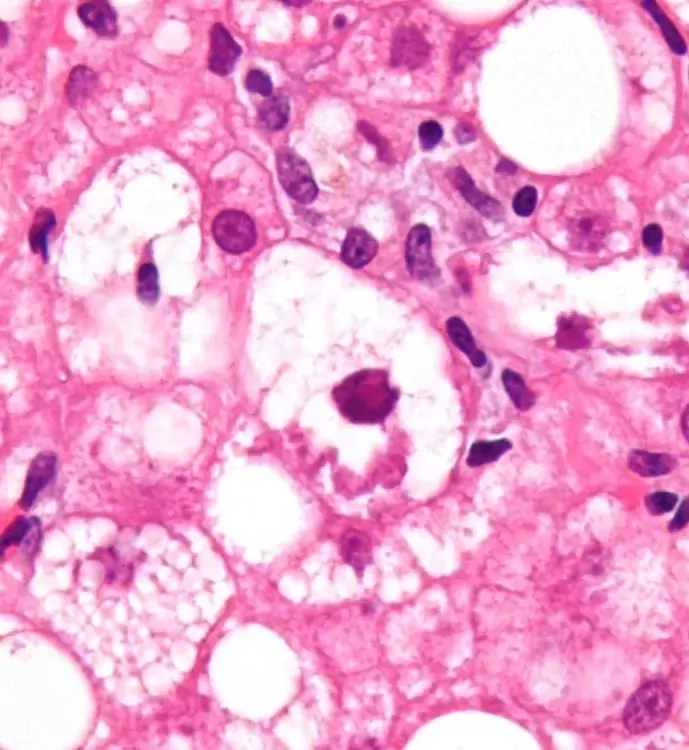

The disease was initially formally known as Primary Biliary Cirrhois (PBC). It has now been changed to Primary Biliary Cholangitis, because it involves a variety of physiological effects—more than just cirrhosis of the liver. Among the general population PBC is rarely found. But as it affects First Nations at a rate of two in every 2,000, the disease develops eight times higher than with non-First Nations people. PBC is even more common in aboriginal communities on the West Coast of B.C., where 48 per cent of Canada’s First Nations people with the disease are located. There is no known cure at this time, though there are treatments for it, and preventative measures, as well.

A significant issue that has come up along the way with PBC, according to Dr. Arbour, is the stigma that it’s associated with alcoholism. Over the years, there have been many misdiagnoses from doctors who wrongly assume the patient developed PBC from alcohol abuse, even in cases where the patient did not use alcohol at all in their personal lives, noted the researcher.

As a result of this, Dr. Arbour and her team have made it their mandate to inform—including educating doctors on the matter—and have created a cultural awareness component to their work on PBC.

“There’s that stigma. Alcohol certainly doesn’t help, but it’s not caused by alcohol… but almost all liver disease is categorized under alcohol-related disease. I think it’s important the First Nations Health Authority are aware of this and involved in care, because this is an autoimmune liver disease,” she said.

When Dr. Arbour and the researchers first started out looking at the disease, and the people who become patients with it, they studied the personal histories of the patients, as well as patients’ medical records, attempting to understand what could have contributed to the development of the disease. The next step was to look at genetic factors, so the researchers searched through patients’ genomes.

The results didn’t show anything truly telling in terms of specific genes that were linked to PBC, but there were a few genes which always seemed to show up, said Dr. Arbour. These genes were slightly different than the genes that showed up in non-First Nations patients with PBC, though the highlighted genes in both populations have the same functions, she said.

“The results we have took a long time to get, mainly because there’s not a lot written about PBC even in the non-First Nations population. More recent studies gave us the background to say this is important, and makes sense, and needs some dedicated attention,” she said.

The next step for Arbour is to pass the buck onto someone else. She believes with the discoveries she and her team have made, she can’t go further in her area, and the project requires an immunologist to take the work on now. Gastroenterologist, Dr. Eric Yoshida, who has been working with Arbour for many years on PBC, will also participate in any upcoming work.

Yoshida has many titles but he is most notably a professor of medicine at UBC, and a liver specialist. He is also quick to share the importance of the disease not being dubbed “alcohol-related” because past mistakes in this area have caused First Nations patients a lot of unnecessary grief.

“Up until recently other specialists like myself, and doctors, didn’t really know anything about the disease. And up until 20 years ago it was assumed everyone with the disease was an alcoholic,” said Yoshida. “It is absolutely not alcohol-related… We strongly believe there is a genetic component,” he added.

Yoshida says that the rarity of the disease makes it more important to understand why it is so high in First Nations populations. He argues that the current statistics on the rates of development are a bit fuzzy, however. The rates of liver transplant referrals are all that the studies have to go by currently, to determine the numbers of people who develop PBC, but it’s possible there are people living with the disease who are not being referred for liver transplants.

Nonetheless, the disease isn’t pretty, or fun, once it’s developed. And it causes a variety of other problems, too.

“The bile duct kind of disappears and it also causes jaundice. In the First Nations population there seems to be more autoimmune liver disease like this, and like autoimmune hepatitis, the cousin of PBC,” he said.