After generations of watching others mismanage their forests, the Huu-ay-aht are seeing themselves in a different position, with a growing stake in Crown land and plans to double the number of citizens employed in the industry.

“Economic reconciliation” was the topic recently addressed during an Island Wood Industries forum in Port Alberni on Oct. 12, which began with words from Huu-ay-aht Chief Councillor Robert Dennis Sr. and Shannon Janzen, chief forester and vice-president of Partnerships and Sustainability with Western Forest Products. Along with Huumiis Ventures, a limited partnership wholly owned by the Huu-ay-aht, Western shares tenure over Tree Farm Licence 44, a 140,000-hectare section of Crown forest inland from Barkley Sound. Contingent on the approval of its citizens, the Huu-ay-aht are looking to have a 51 per cent ownership stake in the TFL 44.

Western works with 45 First Nations across British Columbia, but Janzen notes that the company’s partnership with the Huu-ay-aht is the first to share a tree farm licence.

“This is the largest one that we’ve worked together on,” she said of the collaboration with Huu-ay-aht. “It really is having aligned interests, understanding each other, figuring out a model that works for both parties, and just moving forward together.”

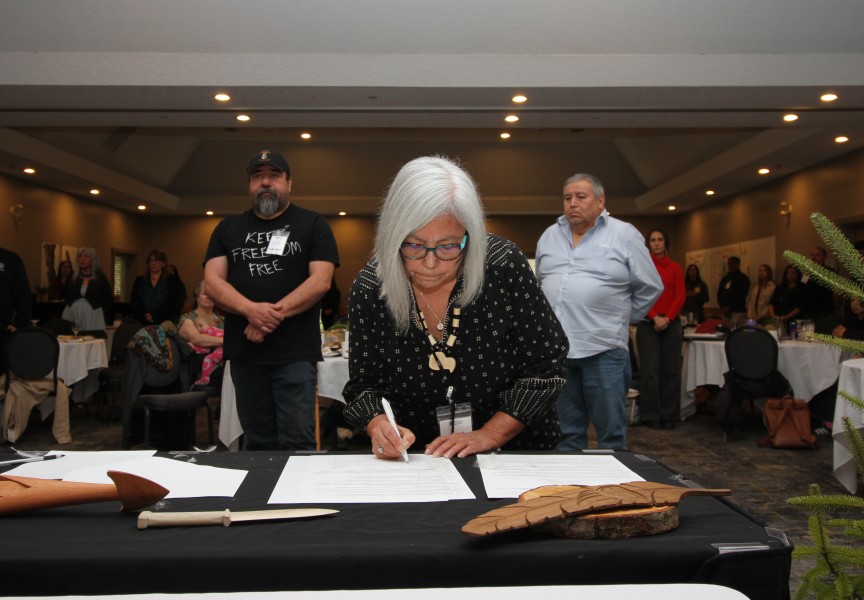

The relationship was solidified in 2018, when the First Nation and Western signed a reconciliation protocol. Since then, the partnership has relied on “a willingness for both parties to change,” said Dennis.

“We used to go to the table with entitlement before. ‘This is Aboriginal title, this is our land’,” recalled the First Nation’s chief councillor. “We really pushed the entitlement agenda, and more recently we decided to have a business agenda, and that’s been the big change for us.”

Their Oct. 12 presentation marked a departure from times when the Huu-ay-aht had no say in how forests in their territory were being managed, with no involvement in the lucrative business being conducted in their own backyard.

This historical inequality was highlighted nearly five years ago in a ruling that came from the Specific Claims Tribunal, a judicial body formed by the federal government to settle matters with First Nations when a resolution has not been reached. The case went back to 1938, when the Huu-ay-aht surrendered all marketable timber on 1,110 acres of reserve land in Barkley Sound to the federal government “to sell in terms most conducive to our welfare,” according details in the tribunal ruling.

Four years later the feds issued a 21-year harvesting licence to Bloedel, Stewart and Welsh, but despite a significant rise in lumber prices, by 1948 no timber harvested from the reserve had been sold. At that time the Huu-ay-aht asked Canada to cancel the licence with the logging company, but to no avail.

The tribunal awarded $13.8 million in compensation to the Huu-ay-aht for Canada’s breach in its duty to the First Nation.

Over the years industrial forestry did develop in Huu-ay-aht territory, and the post-war Vancouver Island giant MacMillan & Bloedell held tenure over TFL 44 from 1955-1999. But by the end of this term logging practices had taken their toll on the Sarita River, considered the most important of the 35 streams in the First Nation’s territory. Sixty-two per cent of the watershed was logged, including nearly all of its flood plain.

What made matters worse was that the Huu-ay-aht saw little economic benefits from the forestry activity.

“We had zero participation in the forest industry,” recalls Dennis of the 1990s.

But in recent years participation has grown to 44 Huu-ay-aht citizens, who work in mills, harvesting or Western’s office. The First Nation hopes to have another 50 of its members employed in the industry in the coming years, a goal that could be reached with mentoring from experienced forestry contractors.

“A lot of the contractors are willing to mentor our people so that they can operate viable businesses,” said Dennis. “It’s going to require the initiative and ambition of Huu-ay-aht people to form contracting companies and submit their names for contracts.”

With multiple companies in operation, forestry currently accounts for 60 to 75 per cent of the total revenue generated by the Huu-ay-aht Group of Businesses in any given year.

Janzen looks back to 2017 for the critical change that occurred between Western and the First Nation, when the Huu-ay-aht purchased the company’s dryland log sorting facility and three properties in Sarita Bay for $3 million.

“There was a big licence holder in our territory. We finally asked ourselves if there was a way we could partner with Western and realise an economic benefit through there,” said Dennis. “I went to Western, not with my hand out, but I went to Western saying, ‘I want to partner with you. What can this mean so I can start to realize the economic benefits that Western realizes?’.”

“At first we were a bit standoffish in thinking, well, this is a core part of our operation, how can that happen in a way that works for both of us?” recalled Janzen. “We just sat down together and committed to finding solutions that work for everyone. It’s a departure from how we’ve done business in the past. It’s required a lot of trust and collaboration.”

Partnering with the Huu-ay-aht has required the forestry company to “think about a whole different path” as it operates in the First Nation’s territory, explained Janzen.

“I think our job going forward, as practices have changed over the last 20 years, is to ensure that we’re maintaining stream health and integrity,” she said.

To help mitigate historical damage in Huu-ay-aht territory, last year Western committed to investing $375,000 towards restoration work in the Sarita, Pachena and Sugsaw watersheds. Within the First Nation’s treaty settlement lands, $5 from each cubic metre harvested is set aside for watershed renewal.

Dennis has already seen an improvement in the salmon-bearing streams.

“We’re seeing a dramatic increase in wild salmon when we do a study of the young smolts in the river, that number is increasing dramatically,” he said. “This year we had a really good chinook run.”