Reconciliation with First Nations was addressed in the opening lines of the Speech from the Throne on Nov. 23, as Governor General Mary Simon read the address to senators and members of the House of Commons to open the 44th session of Parliament. The speech also quickly referenced the discovery of unmarked graves at multiple former residential school sites, news that shook people across Canada this year.

“The discovery of unmarked graves of children who died in the residential school system shows how the actions of governments and institutions of the past have devastated Indigenous Peoples and continue to impact them today. We cannot hide from these discoveries; they open deep wounds,” read the throne speech, which came two months after Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s Liberals secured another minority government in Ottawa. “We know that reconciliation cannot come without truth.”

But as Canada brings attention to the realities that many residential school survivors have known for their whole lives, records of the testimonies that detail atrocities at the institutions await destruction in five and a half years.

Depositions and information gathered by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission are set to be destroyed on Sept. 19, 2027. This follows a confidentiality condition under which former students gave their testimonies, stories that have informed over 38,000 claims made for the commission’s Independent Assessment Process. Along with the Alternate Dispute Resolution claims, the IAP led to financial compensation towards former students according to the severity and extent of abuse suffered, payments that totalled over $3.23 billion.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada was active from June 2, 2008 to Dec. 18, 2015, documenting the history and lasting impacts of the Indian residential school system. Operating across the country from the 1860s to the 1990s, over 150,000 Indigenous children were forced to attend residential schools, including an estimated 3,200 who died while at the institutions, according to the TRC.

The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation was established in Winnipeg to serve as the archival repository of information gathered during the TRC process. Although the national centre can preserve statements from approximately 7,000 people who helped inform the TRC, the destruction of thousands testimonies from survivors means that documents detailing “the magnitude and extent of the abuse” most fully will be lost, according to the national centre.

“The Independent Assessment Process (IAP) records that are set to be destroyed in 2027 hold important information from survivors of residential schools that are vital to uncovering the true history of residential schools and to potentially identifying missing children,” reads a statement from the national centre sent to Ha-Shilth-Sa. “Records analysis requires meticulous investigation work and takes a tremendous amount of time, attention to detail and careful handling of records. Preserving these records would mean more archival research can be done over a longer period of time, potentially uncovering more missing children and more of the residential school history.”

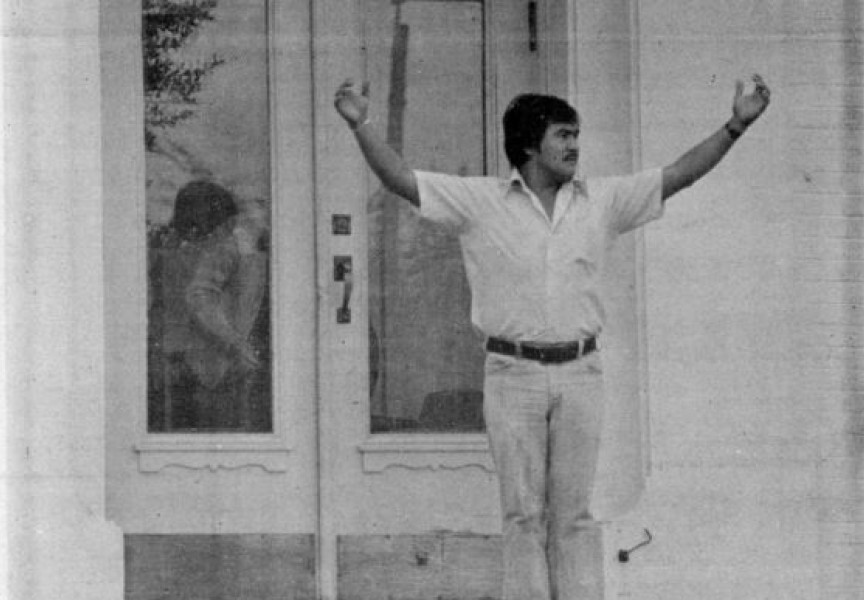

“The general public needs to know what happened,” said Charlie Thompson, who attended the Alberni Indian Residential School as a child. “Because of what’s happening today with children being found, it’s really more important that these records be preserved.”

Survivors can request a copy of their records, or ask that their testimonies be preserved at the national centre in Winnipeg, by calling 1-855-415-4534 or online at https://nctr.ca/records/preserve-your-records/iap-adr-records/. But many survivors aren’t aware of this option, nor were they informed that their stories would be destroyed when testimonies were given, said Thompson. He recalls the IAP process being challenging and confusing for many former students who shared their stories.

“They had a hard time with all of the legal mumbo jumbo that was being thrown at them,” he said. “They weren’t literate. Sometimes they couldn’t even talk, it was so painful for them.”

Barney Williams, who attended Christie and Kamloops Indian Residential School, is fully aware of the approaching destruction date, and had a copy of his records made for his family. As a member of the TRC’s survivors committee, Williams recalls sitting before seven judges when the Supreme Court of Canada weighed the option of preserving the records for history against fulfilling confidentially requirements of the IAP process.

“It was a pretty sad day when we were there in that high court,” he said. “We were hoping they would overturn it, but they didn’t. So there were a lot of upset people.”

“Destruction is what the parties had bargained for,” reads the Supreme Court ruling from 2017. “The IAP was intended to be a confidential process, and both claimants and alleged perpetrators had relied on that assurance of confidentiality in deciding to participate.”

The judgement emphasized the potential harm of releasing the testimonies to the public, noting sensitivities within the churches that ran residential schools and the families of former students.

For example, the Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Sault St. Marie gave up its right to protect against accusations in court.

“[I]t would not have done so were there the slightest possibility that information disclosed within the IAP information could become public,” stated the Supreme Court of Canada ruling.

“[D]isclosure of information contained in the IAP documents could be devastating to claimants, witnesses and families,” continued the 2017 decision. “Further disclosure could result in deep discord within the communities whose histories are intertwined with that of the residential school system.”

The following year an order from the Ontario Superior Court of Justice directed the TRC to undertake a multi-media notice campaign to inform survivors that they have the right to request the preservation of their records. But by 2021 this campaign appears to have had little effect on saving the testimonies for historical preservation. Out of the 70,000 former students who shared their stories, only 27 have had their IAP records preserved with the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation.

Bernard Jack, who attended Christie Indian Residential School as a child, fears history being “brushed under the carpet”.

“I strongly disagree with destroying that kind of evidence,” he said. “I want the Roman Catholic Church to own up to what they did to our nation.”

Thompson doesn’t recall ever being informed of the destruction of his testimony.

“They didn’t tell us that what we’re signing means that at some point your records are going to be destroyed,” he said. “These records are important. My records should be shown, should be read by people that need to understand what we went through as children.”