British Columbia’s largest private landowner, Mosaic Forest Management, is halting logging in nearly 100,000 acres of old-growth forest for the next 25 years.

The forestry company announced the deferral on March 16 and said it’s transitioning to a carbon credit program, which is expected to generate several hundred million dollars in revenue.

Hailed the BigCoast Forest Climate Initiative, Mosaic said it’s the largest project of its kind and is aiming to capture and store more than 10 million tonnes of carbon dioxide.

It’ll be “equivalent to, or exceed what [Mosaic’s] logging revenues would’ve been from logging these stands,” read a release from the Endangered Ecosystems Alliance.

These deferrals will impact old-growth and mature forests on Vancouver Island and Haida Gwaii, including the McLaughlin Ridge, Cameron Valley Firebreak, Cathedral Grove Canyon, lands adjacent to MacMillan Provincial Park and Little Qualicum Falls Provincial Park near Port Alberni.

The Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development said carbon offsets projects are produced and sold under two types of programs: voluntary markets, and regulatory markets.

Mosaic’s project is a voluntary market program certified under the Verified Carbon Standard.

“Voluntary markets enable businesses, governments, non-profit organizations, universities, municipalities, and individuals to offset their emissions outside a regulatory system,” the ministry said. “Under a voluntary market, entities set their own voluntary targets for reducing their greenhouse gas emissions.”

It’s different from a compliance market, where companies need to hit specific emission targets in order to avoid being “penalized by the government that’s regulating them,” he said.

The move is “an important step forward” that allows the forests to stay intact “until they can be protected in legislation,” said Wu.

“We’ve fought hard for decades to keep dozens of these old-growth forests on Mosaic lands from being logged,” said Wu. “From a conservation perspective, 25 years is a big deal because everywhere else, we’re looking at two-year deferrals, or none.”

“If this pans out,” Wu said Mosaic should be “commended.”

Carbon offsets have been criticized by climate activists over a number of loopholes, said Wu.

Namely, that some companies are trying to offset their emissions for forests that were already off-limits to logging. This does not apply to Mosaic’s stated approach, which Wu said is preserving forests that could otherwise be logged.

Garry Merkel, professional forester and B.C.’s old-growth strategic review panel expert, said the shift from logging to carbon offset credits is the “start of a movement.”

The shift, he said, is driven by climate change and “because there’s money in it.”

“Climate change has pushed all of us to start to think really hard about both mitigation and adaptation,” he said.

Because carbon offset programs present a new opportunity to generate revenue, companies, governments and Indigenous groups are able to manage business differently, while still being able to afford to operate, said Merkel.

“There’s little industries that have arisen out of reaction to climate change,” he said.

Despite that, Merkel said large-scale change will require “substantial restructuring of an entire administrative system.”

“Timber is kind of like God in this province,” said Merkel. “It’s a cultural thing because we've grown up with it for so long. We have a very deep bias towards it in the entire bureaucracy, and frankly, in our society at large.”

It’s going to take “real discipline to actually unearth those biases” and make “deep systemic changes,” said Merkel.

The price of carbon is projected to double in the next few years, he said.

That means these trees are worth more standing than they are cut down, Merkel added.

Problem is, he said, “huge infrastructure” relies on logging, and when you factor in the cost of shutting down mills and laying people off it becomes "unaffordable."

And yet, he said “changes don't happen if companies, individuals and groups don't make a number of small pushes.”

Mosaic is an example of a company making “a push,” said Merkel.

The more people that do that, he said, the more it becomes the norm.

Andy MacKinnon, Endangered Ecosystems Alliance science advisor and forest ecologist, said B.C.’s remaining old-growth forests are “critically imperilled.”

“Mosaic's BigCoast Forest Climate Initiative represents a progressive new approach to forest management on private lands in B.C.,” he said. “It's an excellent example of how innovative thinking can lead to new strategies that will yield multiple benefits – social, economic and environmental – from not logging our forests.”

The initiative promises to deliver “real benefits for primary forests throughout coastal British Columbia,” said Katrine Conroy, Minister of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development.

“This innovative approach supports our government’s vision for forestry where we take better care of our oldest forests, First Nations are meaningful partners in forest management, and communities benefit from sustainable, family-supporting jobs for generations to come,” she said.

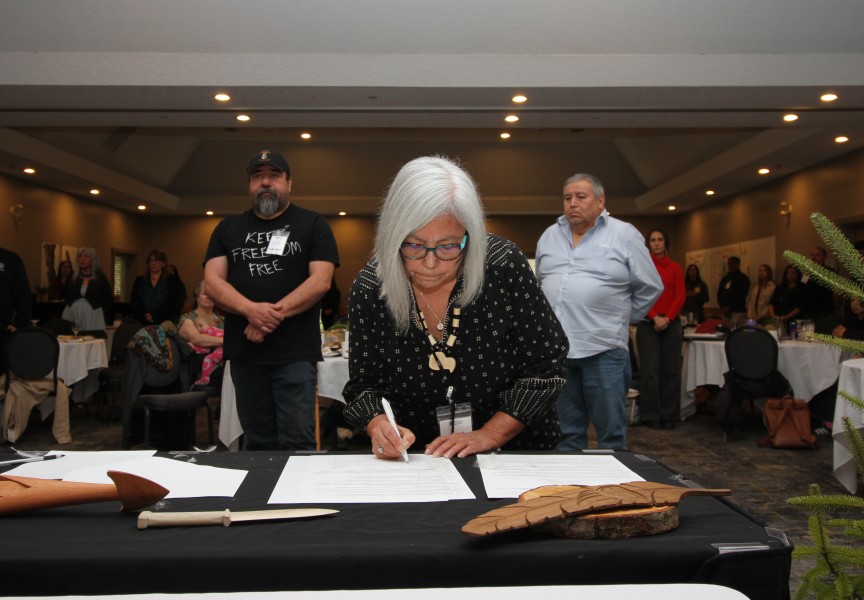

Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council President Judith Sayers said “there is value in what Mosaic is doing,” but questioned the long-term plan.

“What are they going to do after 25 years?” Sayers asked. “There’s still work to be done to make sure they’re not cutting down the old-growth.”

While Sayers said intact forests present an opportunity to expand guardian programs by restoring traditional roles, such as river keepers and forest keepers, deferrals may limit certain cultural practices.

“If it’s a total deferral, we can’t access [the forests] for culture purposes,” she said. “If we defer everything, where are we going to get our old-growth logs for our canoes or our totems?”

Mosaic said it’s in discussion with First Nations about how they’d like to contribute to designing ecological and cultural research efforts that will inform management decisions at the end of the initiative, in 2047.

“Our partnership with the Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas Innovation Program is designed to help implement this research across the entirety of the forests included,” said Mosaic.

The Endangered Ecosystems Alliance said the province has “opened the door to a major policy overhaul in old-growth forest management” by hiring a team to identify 2.5 million hectares of the most at-risk old-growth forests for potential logging deferrals, subject to First Nations consent.

To help finance the transition, the province has committed $185 million over the next three years to provide support for forestry workers, industry, communities and First Nations who may be impacted by the new restrictions.

Meanwhile, the province has not “provided any funds for private land acquisitions, which is needed to buy old-growth forests for new protected areas on private lands, such as these Mosaic lands,” the alliance said.

Sayers said that protecting old-growth forests not only preserves the biodiversity of the region, but the cultural traditions of the First Nations who rely on the ecosystems.

“We need to manage our own forests,” she said. “It has to be up to the First Nations.”