A grey whale came to the shore of Yuquot on Aug. 2, exposing its fins above the surf as the massive animal rolled against the pebbled floor below the surface. The visitation seemed appropriate, as a celebration was underway on the site of the ancient Mowachaht village, where societies subsisted off the passing cetaceans for thousands of years.

“It’s magical for some of you; for some of us, it’s natural,” said Yahtloah, Tyee Ha’wilth Mike Maquinna, about the presence of the whale, before a crowd of over a hundred members of the Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation and dozens of guests.

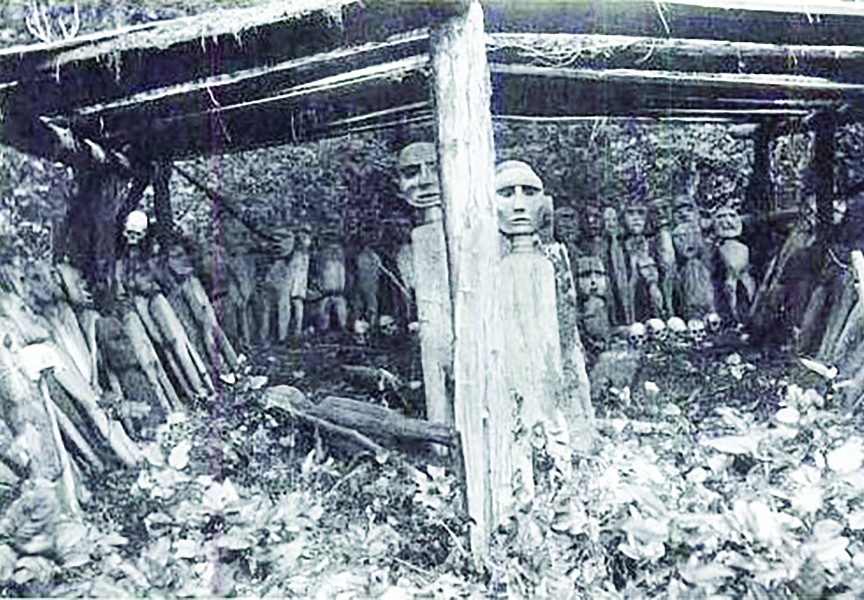

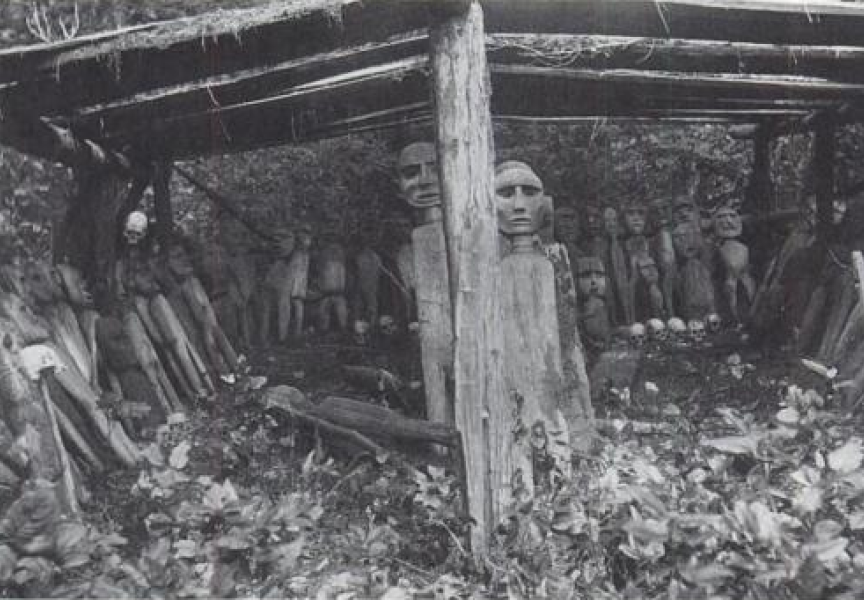

Many of the First Nation’s members had been camping at the site, while others came for the day to celebrate the 33rd Yuquot Summerfest, an annual event held at the Mowachaht’s former village site on the southern shore of Nootka Island. This year the big topic of discussion was the return of the Whalers Washing House, a shrine that was finally returned to Yuquot this spring after sitting in the storage of the American Museum of Natural History for 121 years. In late March the contents of the shrine, which includes 88 carved human figures, four wooden whales and 16 human skulls, were packed up and sent from the New York museum to Yuquot, where they remain in crates awaiting transport to their final location. The First Nation plans to undertake this task over the coming year.

“Now that it’s home we have to decide how we’re going to get it to its original site,” said Maquinna of the sacred contents, which originally were arranged in a secret location on Jewitt Lake.

Very little is known about the Whalers Washing House, as before it was moved in 1903 it was only used by whalers for purification rituals involving a connection to their forefathers. This was a critical part of how they prepared for the hunt.

Somehow George Hunt, a Tlingit-English ethnographer, came across the shrine during his travels. According to historical records from the time, he arranged for the purchase of the shrine with two elders from Yuquot for the fee of $500 – on the condition that the sacred items would be collected while the rest of the village was away on a seal hunt. This purchase was made for the New York museum as it was building its collection from the lives of Pacific coastal peoples. After it arrived at the AMNH the following year, the shrine’s contents would remain in storage, never to be exhibited.

Margaretta James is president of the Land of Maquinna Cultural Society. She said some Mowachaht/Muchalaht chiefs and elders were brought to the museum in the 1980s to see the shrine, some of whom didn’t even know that it existed.

“The museum wanted to replicate it and display it, but that never happened,” said James, noting the longstanding resistance from the First Nation to present the Whalers Washing House to the public.

Many believe that such exposure would rob the shrine of its power, a devastating gesture for a community that has already suffered from the removal of a foundational element of its spiritual lifeblood.

“Bringing our ancestors home is a powerful, powerful thing,” said Mowachaht/Muchalaht member Joni Johnson. “I think this is going to bring us and push us forward in doing many more great things together.”

The need to return the whalers shrine has long been a desire of the First Nation, and was identified in the Yuquot Agenda Paper, a document that the First Nation submitted to the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada in 1997 to gain Yuquot recognition as a National Historic Site. But for decades a consensus couldn’t be reached of how exactly repatriation would occur, until a committee was formed last year.

This group included the new additions of Albert and Alex Lara, a father and son duo from Sacramento, California. Through DNA analysis and the research of church records Albert found himself to be a distant relative of the Maquinna family, several generations after the Mowachaht chief’s daughter and son left Yuquot on a Spanish ship during the late 1700s. They somehow made their way south to California, where Maquinna’s daughter, Izto-coti-clemot, carried the lineage by marrying and having a son.

Having discovered this ancestral relation, the Laras were eager to help. They soon found themselves to be mediators between the First Nation and the museum, drawing on their experience from business and dealing with Indigenous groups in the USA.

“We were able to identify what needed to be done with some actual timelines, really drive it, pull everyone together, be on weekly calls,” said Alex of his involvement. “The desires of the nation and an organization like the museum, there’s some challenges there. It required, I think, some more neutral mediation. I think that was very key in our first meeting in July.”

“We’re here on behalf of our great ancestors to help in any way,” said Albert, as he was on the boat with his son to celebrate at the Yuquot Summerfest. “It became apparent when we found out about how we were related to the nation here, that brought up another type of sense of the human spirit within ourselves. To find out that we could be a part of it in helping, it was the DNA talking within ourselves from our ancestors here to say, ‘Do it’.”

The father and son also acknowledge that the repatriation reflects a broader change among museums regarding the rightful placement of sacred items that might have been removed under suspicious circumstances.

“It’s all about a change in attitude in museums,” said James to the crowd gathered in Yuquot.

“One of the first questions they asked us right away was, ‘What are you going to do with it?’,” she continued. “What I say today is, none of your business.”