On Sept. 30 the annual tradition continued in Port Alberni with a march of orange through the small city’s streets, but this year the procession began at the former site of the Alberni Indian Residential School, walking away from where the institution once stood.

In the morning hundreds gathered around the Maht Mahs gym, one of the two remaining structures from the residential school that operated on Tseshaht First Nation territory for 80 years. Before the walk commenced Tseshaht Chief Councillor Ken Watts announced to the crowd how this year’s event would progress beyond the painful legacy of the Alberni Indian Residential School. Starting at Maht Mahs, the walk crossed several kilometres through Port Alberni along River Road, progressing up Roger Street to pass the Alberni District Secondary School and end at the Athletic Hall.

“We want our survivors to know that that’s where you should have gone to school, you shouldn’t have been brought here from your communities,” said Watts while on the former residential school site, referencing those who attended the institution which closed its doors for good in 1973.

Since 2017 walks have been held in Port Alberni in recognition of those who attended residential school. In 2021 the event was declared a country-wide holiday, as Sept. 30 is now National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. The movement has brought an ideological reckoning for Canada, as the nation undergoes a process of reassessing the forced assimilation of its Indigenous inhabitants throughout the 20th century.

Orange Shirt Day has become particularly prominent in Port Alberni, which housed a residential school in various forms from 1893 to 1973 that came to be known as one of the most notorious in the country for its treatment of students. In his 1995 sentencing of a former Alberni dormitory supervisor, Justice Douglas Hogarth called the residential school system “nothing less than a form of institutionalized pedophilia.”

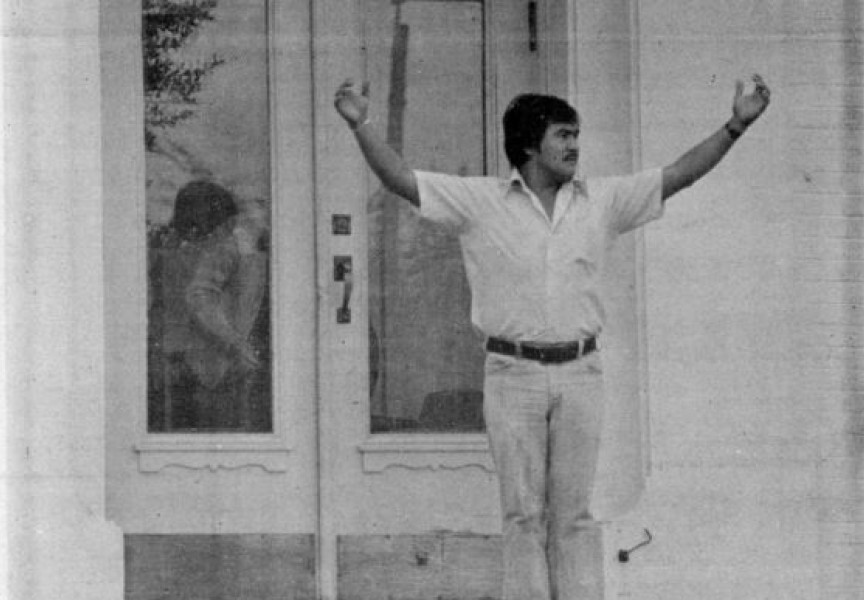

After the conclusion of the reconciliation walk former AIRS student Charlie Thompson stood with other survivors of the residential school to address the hundreds gathered at the Alberni Athletic Hall.

“I want to say to our children, we’re sorry. We let you down. I’m sorry we didn’t teach you to be respectful. I’m sorry we didn’t teach you our language and our culture,” said Thompson. “We weren’t given the tools to be good parents, we weren’t brought up by our parents, we were brought up by an evil institution.”

But Thompson, who has often served as a spokesperson for former AIRS students, also raised his fist to give his peers hope, urging them to say, “I survived!”

“We didn’t deserve to be treated the way we were treated, but we’re here,” said Thompson to the crowd. “Thank you from the bottom of our hearts for being the kind people that you are.”

The Tseshaht First Nation plans to invite AIRS survivors to witness the demolition of Caldwell Hall, a building formerly used as part of the residential school that still stands at the site. The federal government has provided a written commitment to fund this tear down, and awaits quotes from potential demolition companies that are currently being assessed by the Tseshaht.

Watts said this could be done by spring 2026, although the First Nation wants to ensure AIRS survivors will have adequate notice to travel to the event.

While Caldwell Hall is being vacated, Maht Mahs remains a frequent venue for different events. But the Tseshaht have prioritized to also have this former AIRS structure demolished, and hope to build another gymnasium elsewhere on its main reserve.

On Sept. 26 Watts met with federal Indigenous Services Minister Many Gull-Masty to express the need to replace Maht Mahs.

“She heard it loud and clear,” said the chief councillor, although he is concerned when the fiscally tight Carney government would release funds for the project. “They’re looking at making more cuts than actual investments.”

In the meantime, the First Nation has installed a heat pump into Maht Mahs to provide a more manageable temperature in the gym.

“It was so hot in there in the summer, in the winter it was freezing in there,” said Watts. “We’ve got to make do with what we have until we get a new one.”

Whenever the former AIRS buildings are torn down, the First Nation doesn’t plan to rebuild at the site, which lies within its tsunami inundation zone. Instead plans are underway for a memorial park, featuring a totem pole carved in honour of former students from the residential school.

“We’d like it to be a place where our kids can actually enjoy themselves,” said Watts.

Answering a call for others to help in hosting the Sept. 30 walk, Port Alberni Mayor Sharie Minions announced that the city can co-host the event next year.