When you go up the road from the dock to the site of the former Christie Indian Residential School, there is a barely noticeable clearing off the side of the road surrounded by a weathered split rail fence. It is a cemetery with a single stone grave marker and, in another area, a Madonna statue sheltered from the weather by a wooden structure.

Back in the 1980s there were other wooden grave markers but they have since withered and gone back to Mother Earth. The stone cross was lovingly dedicated by the parents of Samson McLean. His school records show his first given name was Bertram and he was only nine when he died in March 1949. The last line on the stone reads, “our beloved one.”

At the back of the cemetery is a wooden board carved with names of some of the students who passed at Christie Indian Residential School, proof positive that children died there and that sometimes their remains didn’t make it back home.

There are seven names on the board with some missing information: Agnes Amos, 1942-1952, Cecilia George 1937-1945, Edith Charleson, Rose Johnson, 1934-1944, Hamilton Charleson, 1944-1948, Reynhold Michael died 1971 and Lorena.

At the healing gathering hosted on Oct. 9 by the Ahousaht Residential School Research Team and the first Nation’s leadership dozens of former students showed up to witness the demolition of one of the last remaining outbuildings that was part of Christie. Some of those that attended did so to honor the memories of their parents or grandparents

Two smaller buildings were already torn down, their rubble left in heaps where they once stood. Organizer Vina Robinson said this was done so that participants could get a better look at the larger building, known as the gym, which was to be torn down that day. According to the Government of Canada, the gym was built in 1923 and contained a bowling alley.

Former students were invited to look inside the gym before demolition began, taken in small groups of two or three. They were allowed to break things if they wanted to. Robinson said that there would be a bonfire where survivors could take things from the demolition piles to throw in the fire, to help them get some closure.

As people came outside from the gym, they were immediately met with cultural workers who brushed everyone off. The organizers were well-prepared with dozens of support workers helping people in many different ways as they went through their emotions.

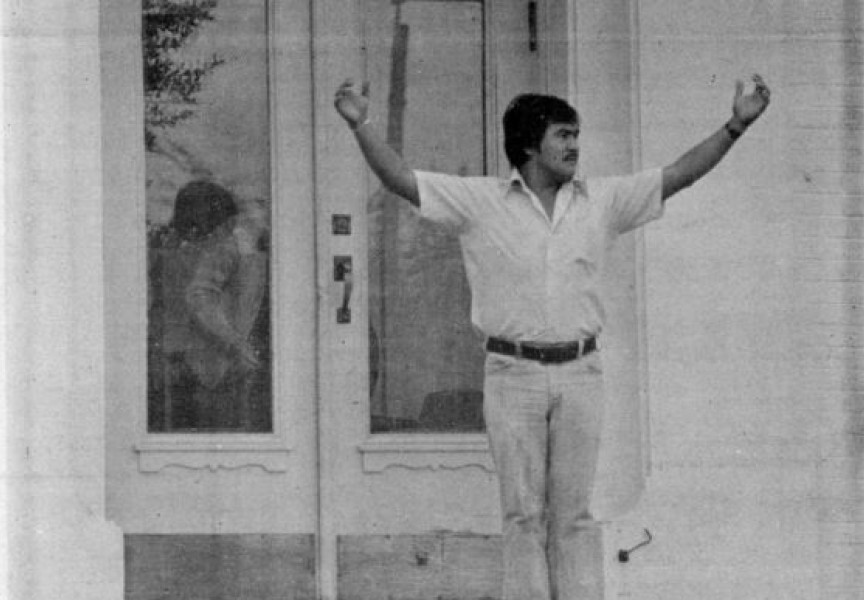

Two of the heavy equipment operators were former Christie students. Bruce Lucas of Hesquiaht and Wilfred Atleo of Ahousaht each ran excavators, tearing down sections of the gym. They were cheered on by the crowd when they exited their machines.

Greg Louie, a former Ahousaht chief councillor and the spokesperson for the event, told the crowd that he was at Old Christie from 1966 to 1970. He said he recognized many of the faces in the crowd as his former school mates.

With the scent of sage and sweet grass wafting through the air, the Ahousaht Ha’wiih and other Nuu-chah-nulth Ha’wiih that were there were acknowledged for being there to support their people. Tyee Ha’wilth Maquinna, Lewis George, was there with his son Hasheukmiss, Richard George.

Members of the August family of Ahousaht stood before the crowd, acknowledging their familial roots to the site.

“There is a stigma attached to this place,” said Ahousaht elder Cliff Atleo.

He said it was the August family that lived there prior to the construction of Christie. Atleo called for healing and the removal of the residential school negative energy from the site.

“Having our language is a sign of resilience. It is who we are and shows our connectedness to the land,” said Louie. “When we got here, they cut our hair, took our clothes, but they couldn’t take away our souls – resilience is the reason we’re here today. We’re still here and we will be here forever!”

During the tour of the inside of the gym, loud bangs, breaking glass and the occasional loud cry could be heard. Excavators began tearing down the building as visitors were fed lunch, observing the work in the cool October sun.

Following lunch, leaders from other Nuu-chah-nulth nations were invited up to blanket their survivors. It was, the Hesquiahts said, a way to comfort the survivor and to let them know their inner child is leaving this place and coming back home.

Her voice heavy with emotion, Hesquiaht Chief Councillor Mariah Charleson said, “My Aunty, uncle and two cousins are buried here.” She noted with sadness that they never came back to their Hesquiaht home.

There were at least 18 Hesquiaht survivors that attended the healing gathering. At least a dozen survivors from the northern Nuu-chah-nulth Nations were blanketed.

When it was her turn to be blanketed, Cathy Michael of Nuchatlaht said her people watched as they tore that “ugly building” down, “Like they tore our lives down!”

Michael went on to say that she has been angry all these years, but she wants to leave that at the site.

With all the residential school unmarked graves denialism happening across the country, it is noteworthy that the Christie Residential School cemetery was built behind the school, specifically for the children that died there.

The Find-a-grave website collects information about cemeteries and records information about burials at each one. It lists 23 memorials at ‘Kakawis Christie Residential School Cemetery’.

The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation lists 46 names, which includes all 23 from Find-a-grave.

They note six confirmed student deaths between the years 1939 to 1941 caused by tubercular meningitis.

Most of the information on the Find-a-Grave memorial site for Christie is complete but there are a few that are not, like the earliest recorded death of Juliana at Christie on September 13, 1903. We don’t know her last name, her birthdate or where her home was.

Also noteworthy is that the students were referred to as numbers in government records. For example, “I have the honour to enclose Memorandum of inquiry concerning death of Pupil No. 250, Cecil Williams, and No. 253, Andrew Tom, both of the Christie Indian Residential School.”

Dated Oct. 2, 1939, the letter was signed by Indian Agent P.B. Ashbridge, and addressed to the Secretary, Indian Affairs Branch, Department of Mines and Resources.

According to federal archive records, some of the deaths were recorded in government and church correspondence. Of those, most were due to tuberculosis, meningitis or pneumonia. One girl died of peritonitis after suffering for days with a ruptured appendix.

In April 2024 Ahousaht delivered a report from their ground penetrating radar scans at the site of Ahousaht Residential School on Flores Island and also at Christie on Meares Island. While they didn’t deliver numbers in their report, they indicated that there are presumed graves in Ahousaht and a cluster of unknown features that need to be investigated further.

Anne Atleo, manager of the Ahousaht Residential School Research Team, has said that further investigation needs to be done and long-term funding and better access to archival material is needed.